Thoughts

From Exam Room to Living Room: The New Health System, Part 1

For the last 50 years, the engine of technology innovation has been a consumer engine. Consumers have steadily accumulated new health capabilities—including diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring—much faster than healthcare organizations. This has caused a decades-old, large-scale migration of health-related activity from the healthcare system to the consumer tech system. But in my experience speaking with hundreds of healthcare CEOs and board members, these migrations remain largely invisible to healthcare leadership.

Digital Coaches, Part III: FDA + Utah Accelerating the Consumer Health Shift

The FDA just updated its General Wellness guidance, allowing consumer devices to measure clinical parameters for coaching—no clearance required. The same week, Utah let AI renew prescriptions with no doctor. Both are doing the same thing: moving healthcare tasks out of traditional systems and into consumer channels.

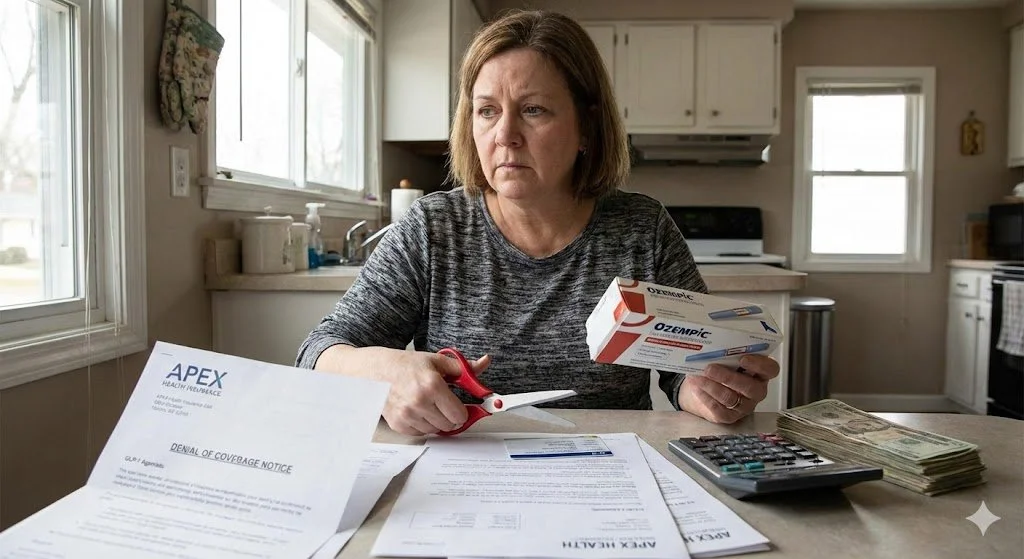

Bad Timing: Will GLP-1s Bankrupt Health Insurance Before They Save It?

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts just posted a $400 million loss—the worst in their history. The culprit? GLP-1 medications that could eventually save insurers billions. The costs hit today, the savings arrive years later, and health systems are caught in the middle.

The First Healthcare Demand Shock of the 21st Century

GLP-1 medications may do far more than treat diabetes or reduce weight. If they substantially cut obesity and metabolic disease, they could trigger the first large-scale decline in healthcare demand seen in the modern era. This piece explores how earlier demand shocks reshaped medicine, why GLP-1s pose a similar challenge for chronic-disease–based service lines, and what hospitals must do now to prepare for a world with fewer cardiometabolic patients.

The New York Times Got Smaller — Healthcare Is Next

The New York Times built one of the best digital products in media—yet its real revenue and profit have fallen by more than half. That’s what disruption actually looks like: the work moves elsewhere while the industry shrinks. Healthcare is now entering the same pattern, driven by consumer tech, GLP-1s, and safer mobility. We’re heading toward better health—and a smaller healthcare system.

Digital Coaches, Part II: Prevention’s New Business Model

Digital coaches are taking prevention where healthcare and public health can’t reach — into daily life. Activity trackers like Apple Watch, Fitbit, and Garmin now deliver personalized, continuous feedback at global scale, turning prevention into a business that keeps people healthier — and needing healthcare less.

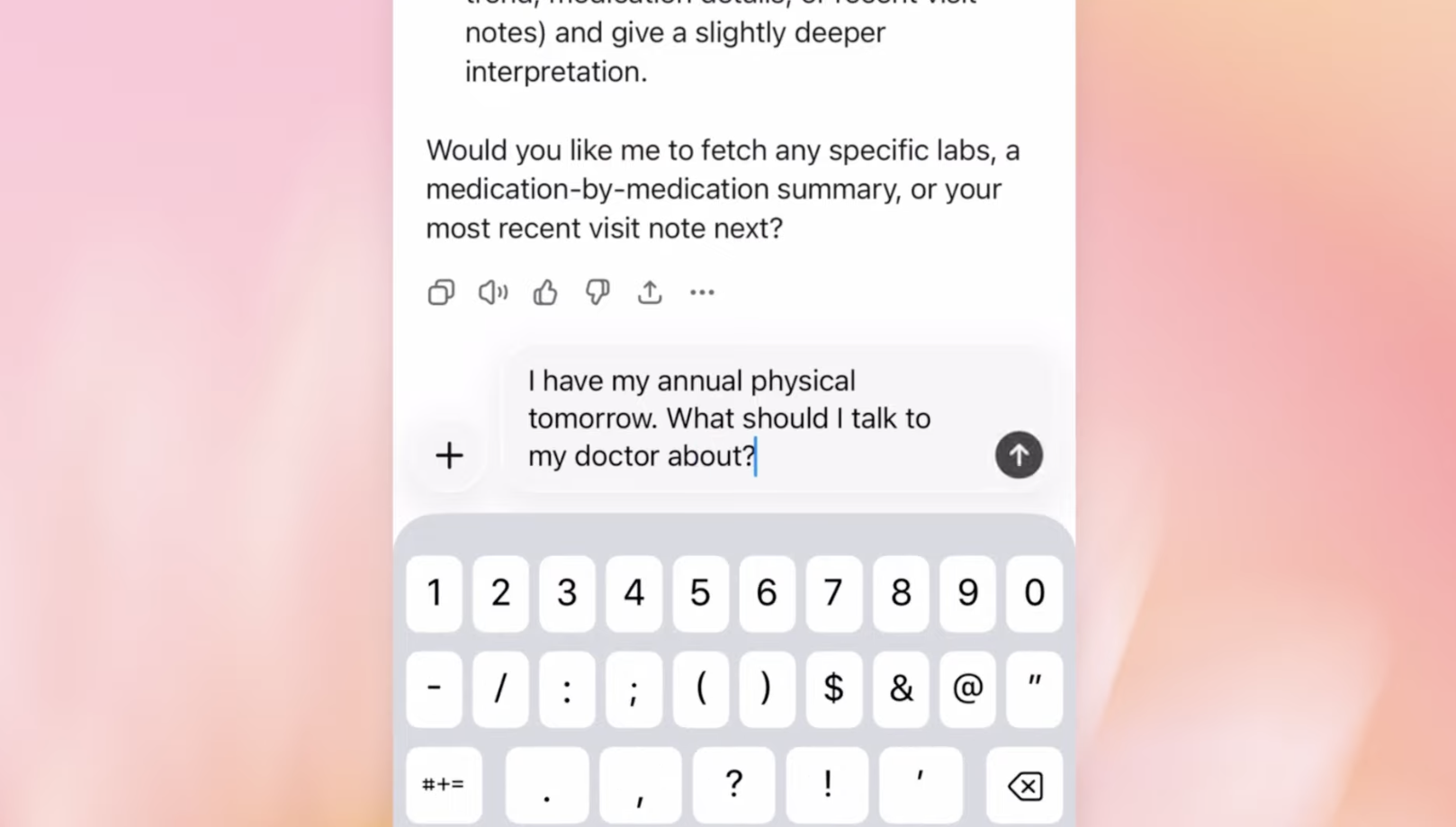

The Rise of Digital Health Coaches

AI health coaches aren’t just for athletes anymore. They’re starting to handle the day-to-day interpretation, advice, and treatment adjustments that once required doctors. From glucose monitoring to hypertension management, technologies like Dexcom, Teladoc, and Omada are quietly taking over the work of routine clinical decision-making. This new generation of digital health coaches marks the next step in a long trend — technology shrinking healthcare by making us need it less.

AI in Coverage Decisions: We Need Guardrails, Not Prohibition

Lawmakers are moving to ban AI-only insurance denials, requiring human sign-off for every case. It sounds compassionate, but it locks us into the same slow, opaque, costly system. The smarter move is AI with guardrails — transparency, audits, and contestable rationales — for faster, clearer, more accountable decisions.

Hidden Connections: What John Muir Can Teach Us About Apple’s New Hypertension Notifications

The naturalist John Muir saw how everything in nature is connected — and today AI is showing us the same truth inside the body. From Apple Watch studies on atrial fibrillation to new hypertension alerts, hidden links in long-collected data are transforming how we understand health.

Fewer Admissions = Fewer Emissions: The Environmental Case for Consumerization of Healthcare

From telemedicine to wearables, fewer clinic visits mean fewer emissions. And as new products like low-carbon inhalers and self-administered HIV therapies move toward over-the-counter access, the environmental benefits of consumerization become even clearer.

Forget the EHR — Your Health Data’s On Your Phone

The overwhelming majority of health-relevant data —movement, behavior, speech, sleep — is now generated outside the clinical setting. As a result, health innovation is increasingly shifting toward consumer devices and tech platforms that actually hold the data — not the EHR or the healthcare system.

Is Autonomous Driving Healthcare’s Most Important Competitor?

Hospitals worry about retail clinics and other healthcare competitors. But real disruption may come from outside healthcare entirely: cars that don’t crash. As autonomous driving becomes safer and more widespread, the revenue ripple effects on emergency departments, orthopedics, and imaging will be profound—and sooner than most systems expect.

The Empowerment of Consumers for Health: A Long Trend, Accelerated by AI

The public conversation about AI in healthcare swings between extremes—some predict it will replace doctors, others that it will usher in a golden age for medicine. So which is it? In my recent American Family Physician editorial, I explore how AI is less a disruptor of doctors than a powerful accelerator of consumer-driven health.

The Coming Collapse of Medical Demand

Innovations like GLP-1 drugs, self-driving cars and AI therapy chatbots are driving down illness, injury and the demand for traditional care. Rather than just improving delivery, these shifts reduce the need for doctors altogether. Snack food CEOs are planning for an Ozempic world. Why aren’t healthcare execs?

Disruption for Doctors 3: the Rise of Selfcare

As AI and smartphones put more diagnostic power into consumers’ hands, healthcare faces disruption not just within the clinic—but beyond it. From OTC drugs to pneumonia-detecting apps, selfcare is rising fast. This isn’t the future. It’s already here—and it’s shrinking the doctor’s role.

Revisited: FDA's AI Medical Device Approvals

One year after analyzing FDA’s AI medical device approvals, a new dataset confirms: growth continues, but acceleration is absent. While more young companies are joining the field, older firms like GE still dominate approvals—classic sustaining innovation. And Big Tech? Still barely on the board.

Disruption for Doctors 2: Healthcare Examples

Smartphone apps that can diagnose pneumonia? FDA-approved machines that can diagnose conditions without a doctor? Robot psychotherapy? It’s not coming, it’s here now.

Disruption for Doctors 1: What’s Disruption?

Most doctors, nurses, PAs, techs, and others in healthcare aren’t familiar with the term “disruption” and are unaware of how technological trends have already begun disrupting their current business models. This post is the first of three that will provide a basic understanding of the term, and the phenomenon.

A Closer Look at FDA's AI Medical Device Approvals (2022)

FDA approvals of AI-enabled medical devices are accelerating—but not in the way you might expect. While new startups are entering the space, the real winners remain legacy giants like GE and Siemens. An analysis of the latest FDA data reveals a classic case of sustaining innovation, not disruption, as established players integrate AI to reinforce their dominance.

CoronaGeddon 2019: Why Every Map You've Seen of the Outbreak is Wrong

Every map you’ve seen of the coronavirus epidemic obscures the progression of the epidemic, rather than informing. Not just one map, but all of them. Let me explain how.