PPE: Land of A Thousand Anecdotes

The Public Demands Data (But Only About Cases and Deaths)

Over the course of the coronavirus epidemic in the USA, we’ve gone through an absolute furor regarding testing. People very rightly understood the importance of measuring the extent of the spread of the virus, and were very rightly outraged by misstep after misstep. CDC, FDA, the President. All played a role in slowing the scale-up and rollout of rapid testing across the country.

Some headlines wondered about the testing directly:

Others talked about the effect of insufficient testing:

The reason U.S. COVID-19 numbers aren’t higher? Not enough tests. (PBS, March 12)

If you’re a data person, perhaps even an epidemiologist, your heart leaps at headlines like these, and public pressure like this . . . because the public isn’t screaming for or against a politician or policy. The public — recently famous for its disgust with experts and science — is screaming for more objective data.

And now, with testing, we actually ARE starting (at least) to have a good amount of tests, and testing, and knowing, for example, whether a death in Seattle is from COVID-19 or some other cause. And that means we can start to better manage this outbreak.

From just the New York Times, we have all this information about cases and testing, updated every single day.

Unfortunately, it turns out knowing cases and tests wasn’t our only lack of data. What else don’t we know? Read on.

PPE Anecdotes ≠ Data

Despite that public furor for more objective testing and confirmed case and death numbers, they haven’t seemed to cotton onto the fact that we need similar information about PPE (personal protective equipment, like masks and face shields and gloves and gowns) to determine how much of a shortage we have, and why

Twitter is ablaze with “we’re out of PPE” anecdotes, including from doctors and other experts. Instead of the data visualizations and dashboards shown above for cases and testing, we’ve got this:

And let’s be clear: there are healthcare workers out there who have gotten sick, and will continue to get sick or even die because they didn’t have sufficient quantities of masks, or gowns, or gloves.

And the assumption seems to be that the solution is: make more masks in the USA. But we don’t know if the overall supply in the USA is high, low, or in-between — or if that’s the source of the problem.

Many hospitals around the country don’t have many COVID-19 patients at this writing — including, incredibly, San Francisco’s UCSF with only 11 hospitalized cases, and DC’s Georgetown with 13. And many (probably most) hospitals in the US are probably not running out of PPE, either, given the very unequal distribution of deaths so far:

What We Need To Know

Just like with cases, we need to know exactly where there is a problem, and why.

Specifically, we need to know:

A - What’s the situation - updated daily

1 - what are the current stock levels of PPE at all major US hospitals, and/or per state

2 - what are the current daily usage levels — most hospitals have protocols that assume an endless supply of masks. Are there ways to modify those protocols to stay safe but use fewer masks? Without question: moving testing to cars in the parking lot, letting patients test at home, etc.

These needed to be updated publicly, by state (at least)

B - What’s the cause - updated daily or weekly

Manufacture is only one part of the chain of activities that determines how many masks there are in any hospital. So we also need to know:

3 - stock levels in warehouses, per state

4 - current production in US per day

5 - current production in China and elsewhere per day. How many are available for purchase?

6 - are there problems in transporting PPE?

7 - what are the protocols used for PPE in testing? Many hospitals in harder hit areas have effectively modified their testing protocols to reduce staff risk while also reducing PPE use (testing patients in their cars, for example). How many hospitals haven’t yet adopted those improved protocols?

If We Don’t Know the Cause, We Don’t Know the Solution

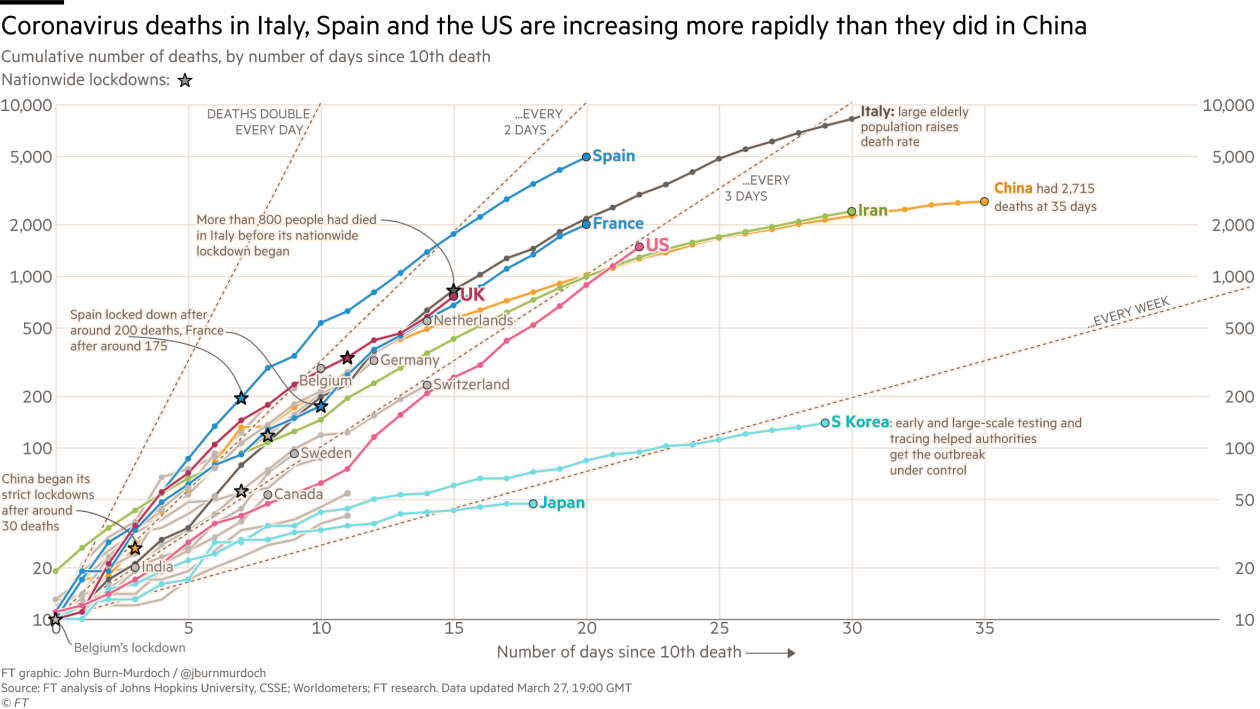

Right now I can get excellent stats on cases/recoveries/deaths/tests for each of the US states and DC (and every country in the world). I can see dashboards with this info, great graphs, all sorts of visualizations, and maps of all colors.

But I have NO idea how many days supply of gowns New York State has. I have NO idea how many masks are being manufactured in the US per day, or in China. I have NO idea if the shutdown has affected the transport and distribution of existing masks in the US or from overseas.

So can we get the Financial Times, and WorldoMeters and, the New York Times, to apply their same investigative and graphic skills to tracking PPE (and ventilators? and other critical materiel?)?

[And since none of those sources are involved in PPE production, their efforts will not slow down our current efforts.]

Because for us to respond effectively and support our hospitals and medical teams, and help the patients they support, we need to get as smart on PPE as we’re getting on cases.