The First Healthcare Demand Shock of the 21st Century

GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy are usually described as weight-loss or diabetes medications. They may turn out to be something more: the trigger for the first large-scale collapse in healthcare demand in living memory

When the polio ward disappeared

““We have succeeded in eradicating smallpox from the world, but in doing so we have put a lot of people out of work—vaccine makers, field workers, and public health officials who dedicated their lives to this fight.” — D.A. Henderson, Director, WHO Smallpox Eradication Program

US polio ward, 1950

Every so often, healthcare experiences a period when demand doesn’t just shift or grow — it collapses. Clean water systems produced moments like this in the early 20th century, when filtration and sewage systems reduced the infectious diseases that once filled pediatric wards, slashing infant and child mortality. Vaccination did the same repeatedly across the 20th century, most visibly with the disappearance of polio wards by the late 1970s in the United States, and with the steep declines in measles, diphtheria, pertussis, and other once-routine childhood killers (though in recent years, declining vaccination uptake has sadly brought some of these risks back).

These were demand shocks of an extraordinary scale — entire categories of disease, and the care built around them, effectively vanished. From 1900 to 1980, annual infectious-disease deaths in the United States dropped by more than 95%. The effect on the healthcare system of the time was profound: diseases that had shaped the daily routine of hospitals — diarrheal illnesses, typhoid, diphtheria, measles, pertussis, tuberculosis — either shrank dramatically or nearly disappeared. Entire service lines lost their purpose.

Because these events unfolded decades ago, we rarely think of them as disruptions to the healthcare system. We remember them only as the public-health triumphs that they truly were, neglecting the healthcare-system-altering contractions they also represented.

GLP-1 drugs may represent our first chance to see something like this happen up close: triumph and challenge rolled into one.

From infectious disease to chronic dependence

That earlier collapse in infectious-disease burden happened while healthcare was still relatively small and still evolving. Hospitals, specialties, and payment structures were in their formative stages. As the disease landscape changed, the system grew in new directions: toward surgery, obstetrics, trauma, and, eventually, toward the chronic cardiometabolic conditions that dominate today.

What emerged over the second half of the 20th century was a healthcare industry whose volumes and revenues depend heavily on long-lasting, slowly progressive disease. Diabetes, obesity, hypertension, atherosclerosis, heart failure, sleep apnea, degenerative joint disease — these are no longer side stories. They are the central plot of modern healthcare.

That dependence is of course not just clinical, but financial. Service lines, buildings, staffing models, and capital plans all assume that cardiometabolic disease will be both prevalent and durable. In effect, the system has built an enormous, expensive apparatus around the expectation that these conditions will be with us, at roughly current levels, forever.

This is the backdrop against which GLP-1s arrive.

GLP-1s and the new demand shock

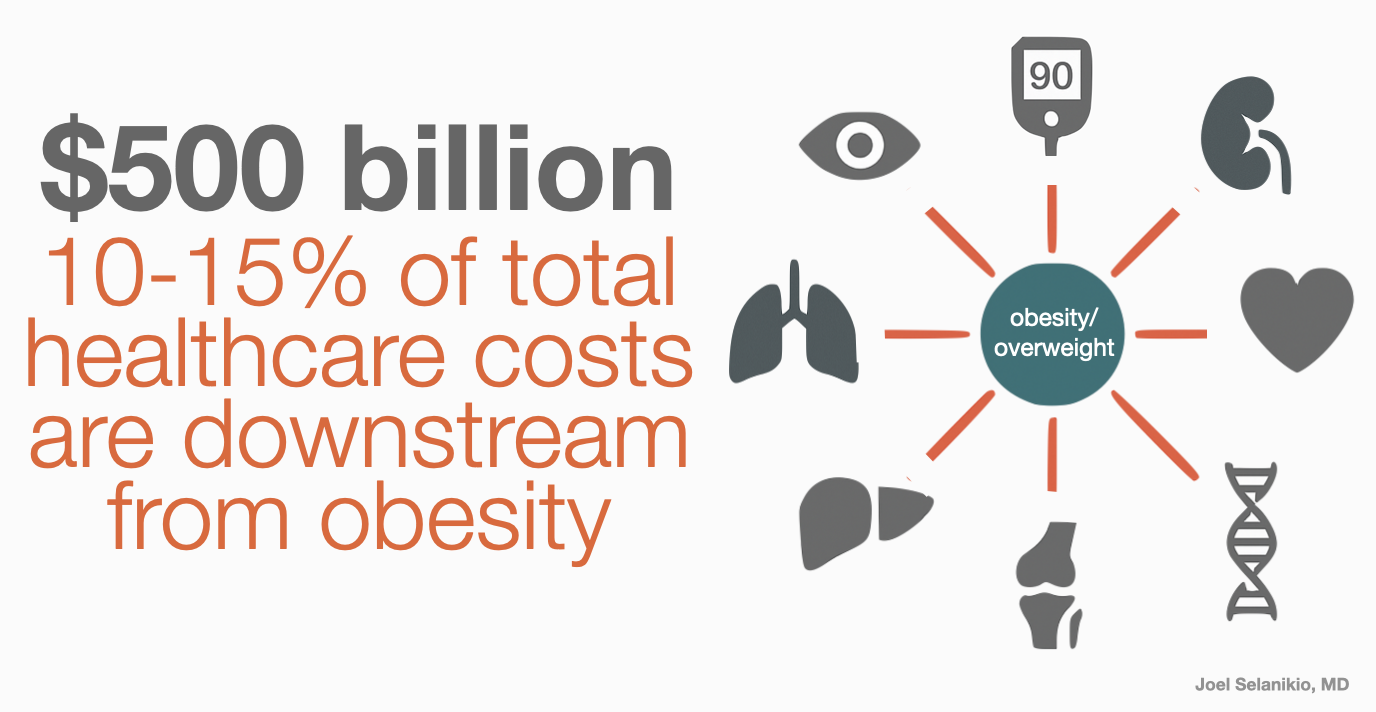

If GLP-1s significantly reducing obesity and diabetes, and everything downstream, that would touch nearly every major service line in today’s system:

Internal medicine and primary care: fewer long-term hypertension visits, fewer chronic medication adjustments, fewer metabolic-syndrome check-ins, and smaller chronic-disease panels overall.

Cardiology: fewer heart attacks and unstable-angina cases, fewer stent placements, fewer heart-failure admissions, and a smaller pool of high-risk patients.

Endocrinology and diabetes care: fewer diabetes-management visits, fewer insulin starts, fewer specialist referrals for complications.

Orthopedics: fewer knee and hip replacements driven by excess weight and joint stress.

Bariatric surgery: smaller candidate pools and lower procedural volume.

Sleep medicine: fewer sleep studies and CPAP initiations as apnea severity declines.

Nephrology: fewer patients progressing to kidney failure through diabetic or hypertensive pathways.

Wound care and vascular surgery: fewer amputations, fewer chronic wounds, fewer revascularization procedures.

In each of these domains, the issue is less disease arriving at the door, year after year. Spread across a decade or two, these reductions would reshape the economic foundation of many health systems.

What happens when your core customers gets healthier without you?

This is the strategic problem GLP-1s create for healthcare: the healthier your population becomes, the less they need the very services your system was built to provide. And if the disease burden shrinks — even gradually — the business model built on managing it must change. Not because care becomes more efficient, but because there is less care to deliver. And unlike the early-20th-century declines in infectious disease, today’s healthcare system doesn’t have the flexibility, margins, or structural slack to absorb a long, steady reduction in the conditions that sustain it.

The question facing health systems is therefore not, “How should we treat patients on GLP-1s?” but, “What happens when the chronic-disease core of our business begins to lighten?”

That is the adaptation problem most leaders have not yet begun to model.

How hospitals can adapt to less disease

So what does adaptation look like in a world where metabolic disease begins to recede?

First, boards and executives will need to take the possibility seriously enough to model it. I’ve spoken with more than 50 healthcare system CEOs about the GLP-1s meds and the possible financial effect on healthcare, and haven’t had a single one tell me they’re working on it. This means no one is asking “what if the GLP-1 meds do exactly what they seem to do?” What does your financial and clinical picture look like if, over ten to fifteen years, the prevalence and severity of obesity-related conditions in your catchment area decline meaningfully? Which parts of the system end up built for more patients than are showing up?

Second, systems will need to rebalance toward areas of enduring or rising need. Even in a healthier cardiometabolic world, there will be no shortage of dementia, cancer, complex geriatric care, behavioral health,, and palliative needs. Many of these are currently under-resourced relative to demand. If GLP-1s bring fewer diabetic amputations and fewer heart-failure admissions, that becomes the moment when health systems must decide whether the resources they free up simply evaporate — or get deliberately redirected.

Finally, this is an opportunity to align with demand elimination rather than resisting it. If GLP-1 meds continue to prove effective on-balance, and continue to improve, the smart move might be to integrate them: building programs around metabolic health, monitoring, side-effect management, and long-term risk reduction, even as the need for traditional downstream procedures shrinks. Though, as I’ve mentioned in other posts, healthcare systems that do this will be in competition with lots of startups trying to do this with wearables, AI, and other new tech.

The choice ahead

GLP-1s may trigger the first major decline in chronic-disease demand that modern healthcare has ever faced. The question is whether hospitals and health systems prepare for that shift by redesigning capacity, workforce, and strategy — or simply wait for volume to erode.

The systems that plan for a world with less metabolic disease will be the ones that remain viable in it.