The New York Times Got Smaller — Healthcare Is Next

Better product + bigger audience = a LOT less money?

The New York Times is often held up nowadays as one of the great success stories in an otherwise decimated journalism industry. Articles highlight growing subscriber numbers, rising digital revenue, and a product that looks far better than the paper of twenty-five years ago.

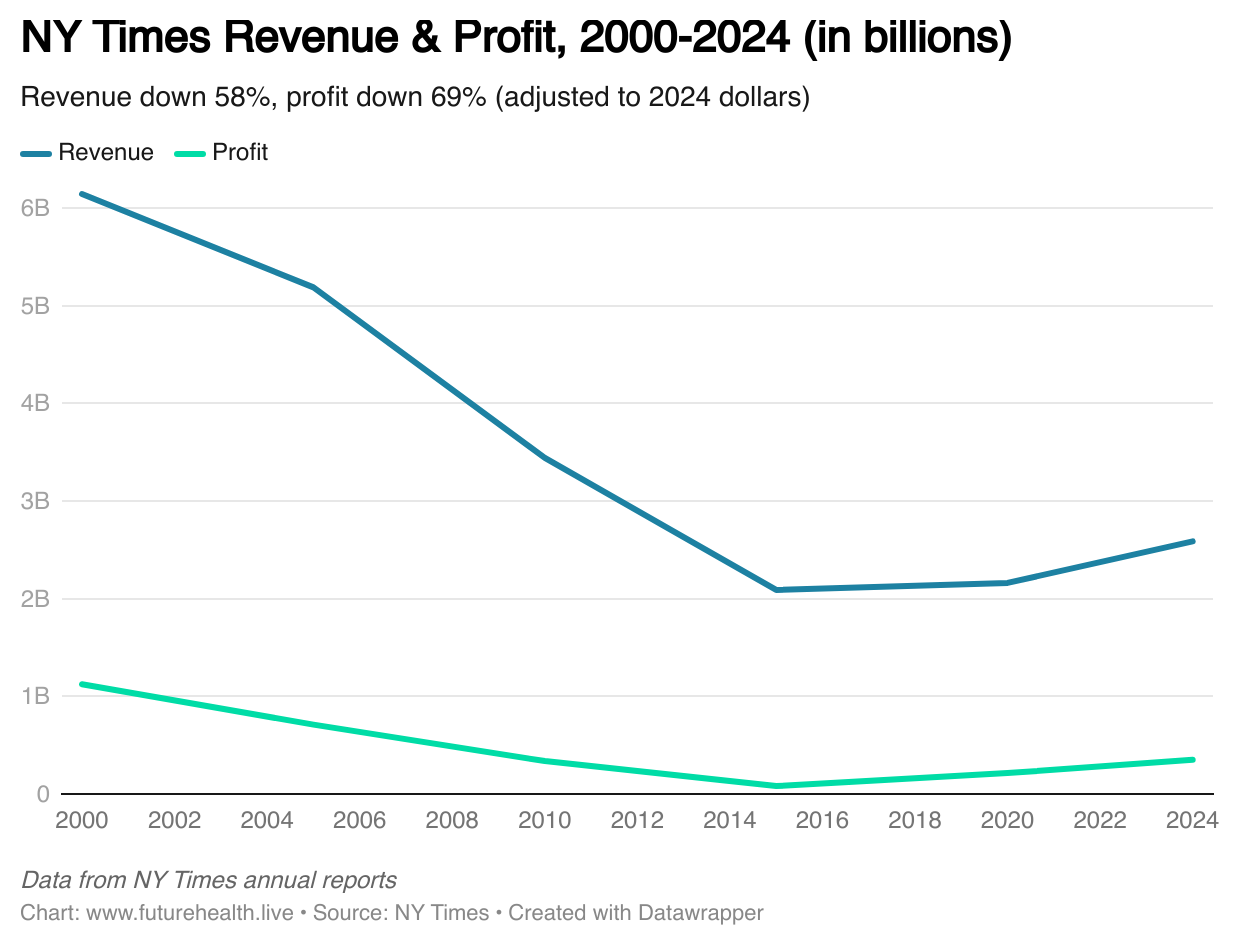

But if you look at a chart of their revenue and profit over that period, the pattern is unmistakable: real revenue is down nearly sixty percent. Real profit is down about seventy percent:

So while it’s true that the Times has built one of the best digital products in media, reached more readers than ever, and maintained a high standard of journalism — it’s also true that it is a shadow of its former self.

Disruption doesn’t kill the work — it moves it

In a nutshell: faced with digital disruption, the Times made a better product, delivered it to a bigger audience, and ended up with a lot less money.

That combination — better product, shrinking economics — is exactly what disruption looks like in the real world. The work that used to sustain the industry is now done somewhere else, by someone else, and — at least in the case of digital disruption — often for free.

Steel followed this pattern. Music followed it. Newspapers followed it. In every case, the consumer gained access and capability, while the incumbent industry saw its total market shrink. The integrated mills didn’t expand when minimills took the easy jobs. Record labels didn’t expand when digital distribution flattened the business.

And the internet didn’t erase the functions of a newspaper. It just pulled them out of the newspaper business. News now breaks on Twitter, analysis lives on Substack and podcasts, classifieds moved to Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace, and most daily information comes from apps. The work didn’t vanish. It simply moved outside the industry, leaving the industry itself much smaller.

Just history repeating

By all indications, healthcare is heading down the same well-worn path of disruption.

A large fraction of modern healthcare consists of informational tasks: explaining symptoms, interpreting labs, adjusting medications, and handling the low-level worries that humans generate every day. And as AI models, sensors, and apps continue to improve, a great deal of this informational work will move outside healthcare entirely. Not to another clinic or another clinician — simply out of the system.

Even if that were the only force at work, it would be enough to shrink the system. But consumer health technology isn’t the only powerful force at play here.

Winter is coming

It is becoming clear that GLP-1 medications and other metabolic therapies will reduce the number of people who ever develop the conditions that currently drive much of healthcare’s revenue: diabetes, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease, severe obesity, osteoarthritis requiring surgery, several cancers, and the cascade of complications that accompany all of them.

In fact, Swiss reinsurance giant Swiss Re projects that GLP-1 drugs could by themselves cut US mortality by as much as 6.4% over the next twenty years (!).

Of course, the people who do reach the hospital will still need expert, highly specialized care — the kind that only major medical centers can provide. Cardiac surgery, transplants, trauma care, critical care, oncology, neurosurgery: none of that disappears. It remains essential.

But fewer people will arrive there if their health is better to begin with.

And it isn’t just GLP-1 meds.

Driver-assistance and autonomous driving systems are steadily reducing serious accidents — one of the biggest sources of high-acuity utilization. Fewer crashes means fewer surgeries and fewer long recoveries. Add this to consumer health disruption and the GLP-1 meds and the direction is obvious: people will need less from the healthcare system.

“In the 30 years from 2021 through 2050, ADAS [advanced driver assistance systems] technologies ... are anticipated to prevent approximately 37 million crashes, 14 million injuries, and nearly 250,000 deaths.”

In a nutshell: consumer health tools are beginning to replace the everyday questions, new drugs are starting to reduce the chronic diseases that still dominate healthcare’s workload, and safer vehicles are steadily reducing the accidents that still generate so many trauma visits and surgeries.

Healthcare has no Wordle - and that’s a problem

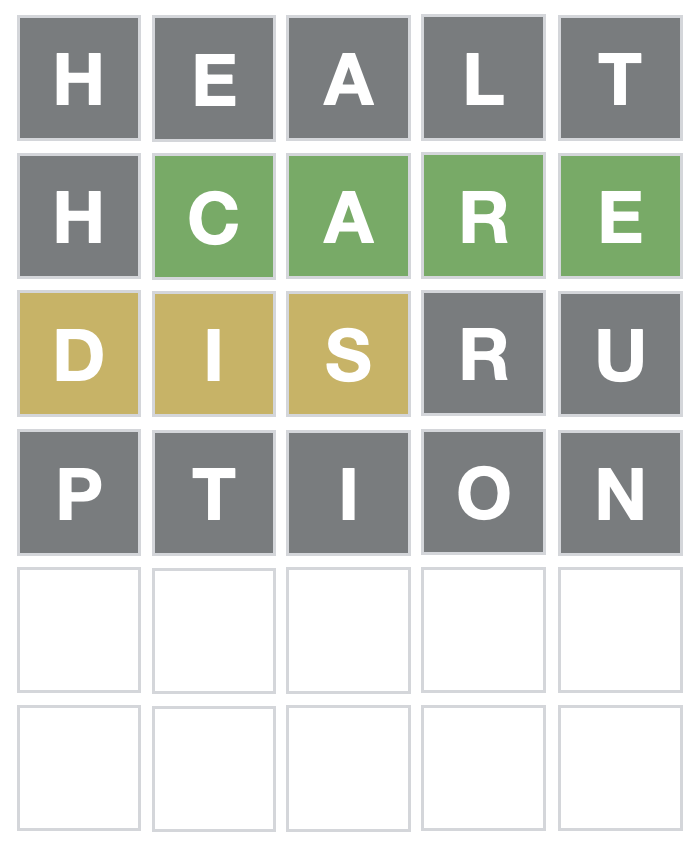

When demand for newspapers collapsed, the Times cushioned the decline by expanding into things that had nothing to do with journalism: games, recipes, product reviews. Wordle didn’t save the economics of journalism, but it created a daily ritual that kept people connected to the brand even as the underlying business shrank.

Healthcare has nothing comparable.

No sideways expansion into a consumer-friendly category.

No Wordle or NYT Cooking or Wirecutter.

If you squint, you might imagine a hospital-branded, medically supervised fitness center, or nutrition programs built around metabolic science. Interesting ideas, but not likely to succeed at scale, and not playing to healthcare’s strengths.

As noted, healthcare does have a core that will remain — complex surgery, trauma care, critical care, oncology. But that core isn’t a cushion; it’s the remnant. And even that remnant will shrink as ADAS reduces trauma, GLP-1s cut metabolic disease, and AI and robotics continue reducing the need for invasive procedures. None of this high-acuity work can become healthcare’s Wordle. It isn’t lightweight, pleasant, cheap, or scalable. It can’t serve as a daily — or continuous — ritual that keeps millions connected to the system when they don’t need the system.

A Better Healthcare System — and a Smaller One

The New York Times today is a much better product and a much smaller company — and it’s the success story of journalism, an industry in which many newspapers simply disappeared, while others have just become a place to view Google ads.

Healthcare is now moving along the same trajectory, except the forces pushing it downward are stronger and the sideways options are fewer. More questions answered outside the system. Fewer chronic diseases progressing to advanced stages. Fewer car crashes sending patients to the trauma team.

We are heading toward a world where people truly need less from the healthcare system.

That is good news for our health, but it will not feel like good news to the institutions built for a very different era of demand. A system built on high volume, chronic disease, and constant incoming problems is not prepared for a future defined by less of all three.

The uncomfortable question — and one that healthcare leaders will eventually have to confront — is this:

What does a health system plan for when its business model shrinks faster than its mission?

That question shapes the future of healthcare.

And it is the lesson of the Times.