Digital Coaches, Part II: Prevention’s New Business Model

In The Rise of Digital Health Coaches, I described how digital health coaches from companies like Teledoc, Dexcom, and Omada Health are taking over functions once handled by clinicians — interpreting readings, recommending actions, and closing feedback loops. These tools live outside healthcare, and they are directly pulling activity and revenue out of it, expanding the reach of consumer health empowerment (i.e. “Dr. You”).

I ended that post by promising to explore how consumer-focused digital coaches are reshaping health for everyone—not just patients. These coaches aren’t directly challenging healthcare, but in the long term may reduce dependence on it.

Prevention has always been better — but harder

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Everyone knows the phrase. Few systems live by it.

Healthcare has always been organized around illness — responding after something goes wrong. Prevention works earlier, acting before illness occurs.

Old school public health: still essential

Traditional public health achieves that prevention through collective infrastructure, regulation, and policy: clean water, sanitation, vaccination, pollution control. The new prevention is digital, built on wearables and other consumer technologies. It doesn’t replace those foundations — we still need vaccines and clean water — it extends them to the individual level.

It focuses on what public health has always found hardest to reach: the daily behaviors and decisions of individuals, shaped by personalized, continuous feedback and advice.

The new prevention sits outside both healthcare and public health, reaching people directly through their devices — every day. It’s the missing last mile of behavior.

From chronic disease to continuous prevention

The first generation of digital coaches grew up inside medicine. Companies like Livongo (now part of Teledoc), Omada, and Virta use connected sensors and human coaches to help diabetic or hypertensive patients stay on track between healthcare visits.

The next generation has moved beyond disease. It focuses on continuous prevention — helping people improve their activity, the behavior most reliably measured by today’s devices and most consistently linked with long-term health.

Inside healthcare, prevention was something doctors advised but rarely measured or were reimbursed for. Outside healthcare, it has become a major product: quantified, personalized, and available to everyone with a phone (which is to say, everyone).

This is both because the addressable market includes both the sick (as with healthcare) and the well, and because it doesn’t require dealing with healthcare’s substantial regulation and paperwork.

The new consumer coaches

A growing group of products now provide preventive guidance and feedback based on activity. Together, these products represent prevention delivered continuously, outside healthcare and without clinicians. Meta-analyses across brands confirm increases in daily steps and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA):

“Activity trackers appear to be effective at increasing physical activity in a variety of age groups and clinical and non-clinical populations. The benefit is clinically important and is sustained over time. Based on the studies evaluated, there is sufficient evidence to recommend the use of activity trackers.” (Ferguson et al, Lancet Digital Health 2022)

Activity trackers

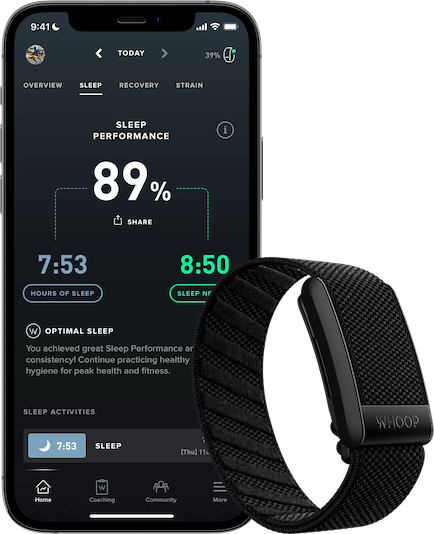

Whoop app and device

Apple Watch uses activity rings and reminders to nudge users toward daily goals (it has a new AI-powered “Workout Buddy”, too, but that focuses on exercise, rather than on regular daily activities). Data from the Apple Heart and Movement study of 160,000 users confirmed that closing rings and related nudges increased movement and reduced sedentary time. [Note: I am a happy Apple stockholder of long duration]

Fitbit (now part of Google) has also been shown to produce an increase in steps, MVPA, and a decrease in weight.

Garmin Connect occupies the same category of mainstream trackers as Apple Watch and Fitbit, and likewise has mounting evidence for increasing activity.

Oura Ring extends coaching into sleep and recovery. While I was unable to find any research that Oura’s version of tracking and coaching increased physical activity (I’m very open to correction on this) there is no reason to believe that it would not produce similar results to the other devices.

WHOOP, maker of another wrist-worn device, has published research showing that more frequent WHOOP wear was associated with lower resting heart rate (RHR), higher HRV, longer sleep duration and increased physical activity.

There are, of course, many other examples in this category: more rings, more watches, more trackers.

Beyond activity trackers

There are exciting developments happening in sleep tracking, and in metabolic guidance, from companies like Eight Sleep and Lumen. I’ll detail these in a future post.

Closing the action gap

In Part 1, I described the interpretation gap — the distance between mountains of raw data and scalable actionable insight. The next challenge is the action gap: turning that insight into sustained activity and habit. As an example, Apple’s data shows that their 'Time to Stand' watch reminders reduce sedentary behavior by 12%.

All the products mentioned above address this action gap through behavioral design rather than medical authority or public health regulation. They deliver timely, specific, and continuous feedback—something healthcare has never been structured to provide.

Timeliness keeps users engaged. Specificity makes action clear. Continuity sustains momentum. Each of these supports the broader cycle that defines digital coaching: measure, interpret, act, and repeat.

What the evidence shows—and what it doesn’t

To summarize, the evidence from these device-software combinations now supports several clear points:

Behavior change is real. Randomized and observational studies show sustained increases in daily activity and improved sleep when coaching features are active.

Physiologic benefits follow. Users show lower resting heart rate, higher HRV, and better aerobic capacity—objective markers of improved cardiovascular health.

Clinical endpoints remain unproven. Whether these preventive gains translate into lower disease incidence or mortality will require longer follow-up.

But the early signal is unmistakable: selfcare can produce the measurable improvements that healthcare has always wanted but struggled to deliver.

Oura ring

The economics of selfcare

For the companies building these tools, prevention isn’t charity or a government function — it’s a business. And a simpler one than healthcare ever allowed.

No billing codes. No licensing fights. No waiting for a CMS rule change that never comes. A $200 device or a $10/month subscription delivers the kind of daily guidance that doctors wish they had time for—and that no insurer will pay them to give.

The market is the part healthcare never served: the well, the worried-well, the “I should probably move more” crowd. Doctors see the sick. Prevention sees everyone else, every day.

| Healthcare prevention | Digital selfcare | |

|---|---|---|

| Reimbursement | ~$0 for “walk 30 minutes” | $100–300 one-time, $0–120/yr |

| Marginal cost per user | High (time, staff, charting) | Near-zero |

| Who it reaches | Patients with a diagnosis | Anyone with a phone |

| How often | Once or twice a year | Every single day |

This is classic Clayton Christensen new-market disruption. These coaches aren’t taking patients away from doctors—they’re turning people who never had a coach into customers. Most of us will never pay $150 for a trainer to tell us to stand up, once. But we’ll pay $250 for the watch that does it at 2 PM, every single day.

The flywheel is quiet but real: more movement → better data → sharper advice → more movement. Apple closes ten billion activity rings a day. Fitbit counts a hundred trillion steps a year. No health system can match that cadence without spending itself into the ground.

Prevention, after decades of slogans, finally has a business model that works.

Healthcare’s death of a thousand cuts

Above, I said that these coaches aren’t “directly taking customers from healthcare incumbents” — and that’s true. But indirectly, they pose a distinct threat to healthcare incumbents in the same way that the GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic do: by making people healthier and reducing their need for care.

Down the line, every extra thousand steps is one less stress test, one fewer statin, one less procedure. A slow, steady shift: healthier people, smaller healthcare bills, and revenue that flows to the device in your pocket instead of the clinic down the street.

Prevention, after decades of talk, finally has both a delivery mechanism and a business model. And every success story outside healthcare makes healthcare itself a little smaller.

The pattern continues

We’ve seen this progression before:

Knowledge moved out of institutions with search.

Measurement moved out with wearables.

Interpretation moved out with AI.

Now behavioral change — the essence of prevention — is moving out through digital coaches.

Each step makes individuals more capable on their own and shifts both activity and revenue away from healthcare and toward Doctor You. And the technologies transforming health aren’t making healthcare better. They’re making people better—so they need healthcare less.

That’s the trajectory of selfcare, and the quiet revolution of digital coaches.

Good advice — increasingly supported by data