From Exam Room to Living Room: The New Health System, Part 1

For the last 50 years, the engine of technology innovation has been a consumer engine, as the biggest markets for computers shifted from government and corporations and universities to individual consumers. Simultaneously, innovation in information technology has meant that IT has been the primary way that we all acquire new capabilities. Combining these facts has meant that consumers have steadily accumulated new capabilities—including capabilities related to their health—much faster than institutions, including healthcare organizations.

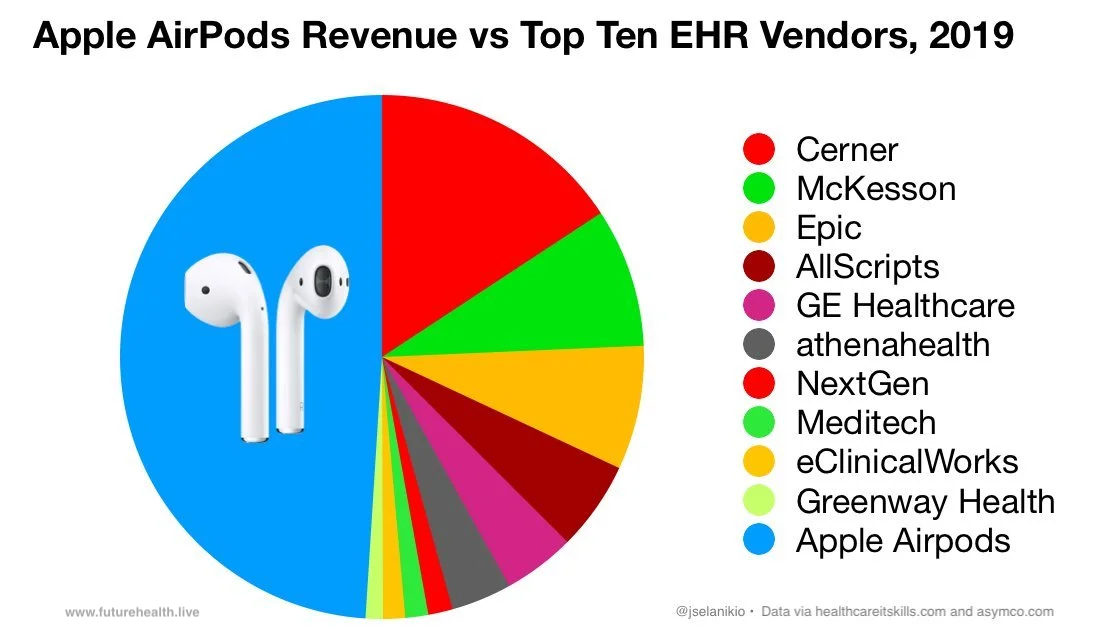

This is a lesson that healthcare has not yet absorbed. They think that Epic, leading EHR maker, is a health software giant that will lead in applying AI to our health—not realizing that Apple and Google are now health companies and orders of magnitude larger. As I wrote in Forget the EHR — Your Health Data's On Your Phone:

What does it mean for the future of health when Apple makes more money from AirPods than the top ten EHR vendors combined?

That comparison matters because consumer technology companies have become health companies—whether they call themselves that or not—with more money, more programming talent, and more access to the population than any EHR company or healthcare system.

This is even more significant in the AI era, because AI innovation requires data, and we now have 50,000 times more consumer health data than EHR data, simply because there are more consumer computing devices—including phones constantly measuring and recording our speed, direction, and frequency of movement.

And this has caused a decades-old, large-scale migration of health-related activity from the healthcare system to the consumer tech system—to devices, apps, and AI with no provider involved at all.

Five Tasks Migrating Out of Healthcare

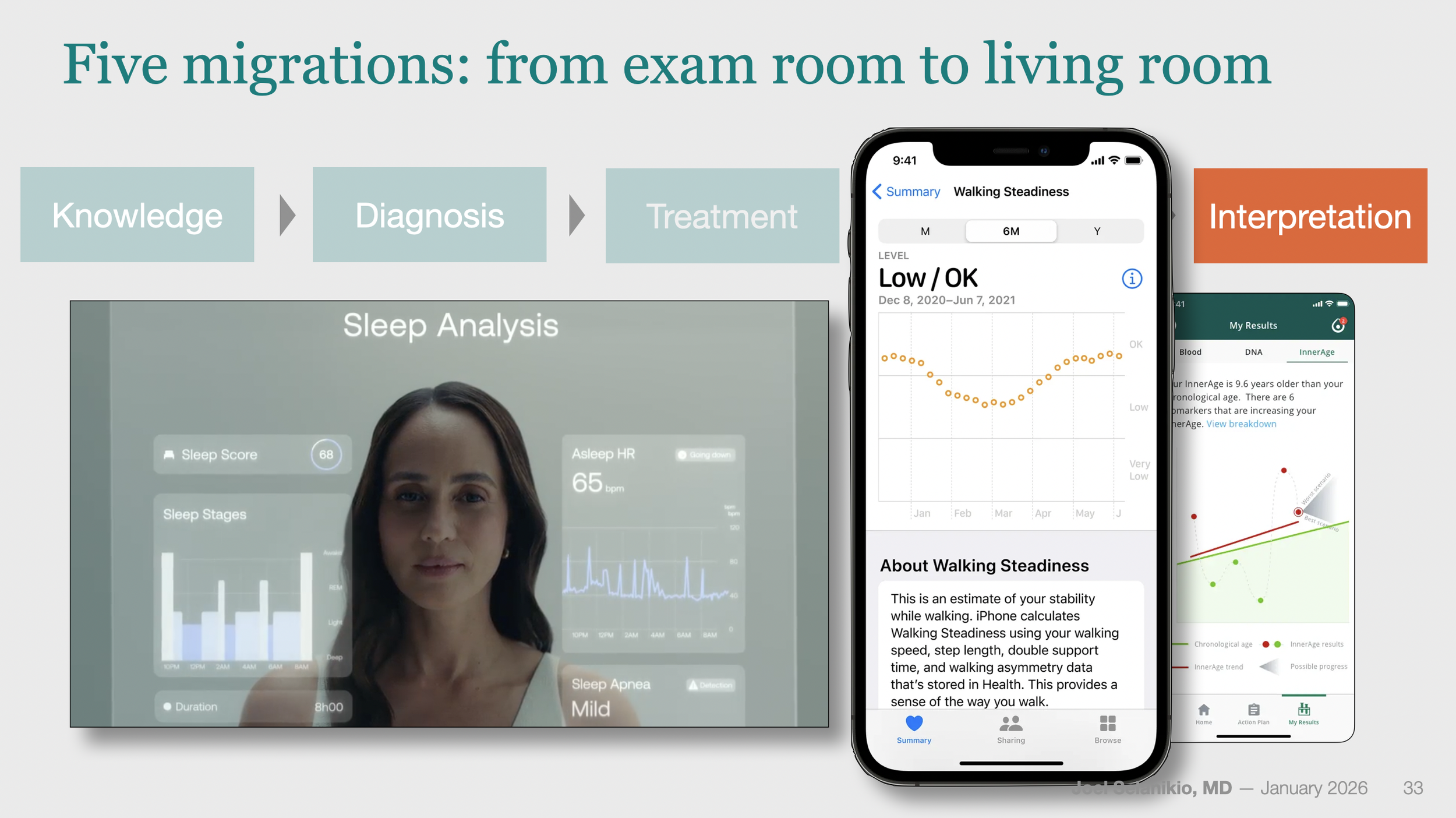

One way to think about the migration is by core healthcare tasks: knowledge, diagnosis, treatment, monitoring, and interpretation. Over decades, portions of each have steadily migrated outward from clinics into homes. Not all at the same speed, but all moving in the same direction—from clinic to home. From provider-mediated to no-provider-involved.

And never the other way around.

Knowledge

Patients have always been interpreters of their own symptoms. What changed with the Web was the amount of context available before involving a clinician. Suddenly, around 25 years ago, consumers had access to the same medical reference material as clinicians, via websites like drugs.com, Medscape, and of course Google.

None of this replaced clinicians—it simply gave the patient information. But across multiple studies in systems like Kaiser, the NHS, and others, a universal finding is that giving consumers reliable medical information consistently reduces low-acuity in-person visits—millions per year in the US.

Diagnosis

It started in the 1970s with home blood pressure cuffs, primitive glucose meters, and early pregnancy tests. Now the category has exploded: direct-to-consumer lab testing, rapid covid and flu tests, continuous glucose monitors. Twenty million home pregnancy tests are sold annually in the US—each one representing a service that once required a clinic visit.

Consumer devices now perform complete diagnostic functions that once required clinic visits and specialized equipment. The Apple Watch can detect atrial fibrillation and, with new apps, perform a complete sleep study—not just collect data for a physician to interpret, but deliver the diagnosis to the user. Hearing tests used to require trained personnel and expensive equipment; now you can do them with AirPods and your iPhone.

Consumer tech is also providing health services that were never really practical before: Samsung, for example, has announced that its phones will be able to screen for early signs of dementia from the language we use in our communications. Every day, all day, not just at a once-a-year checkup.

Treatment

Just this month (January 2026), Utah became the first state to allow AI to legally write prescription renewals for chronic medications: Doctronic’s AI platform, with no human provider in the loop, can now renew prescriptions autonomously within the state's regulatory sandbox. Arizona, Texas, and Wyoming are exploring similar approaches. Back in 2019, the FDA under Scott Gottlieb was reported to have been looking at this kind of "autonomous prescribing," and those discussions are becoming reality.

But AI-assisted treatment is just the latest chapter in a much longer story that predates AI. In Disruption for Doctors 3: The Rise of Selfcare, I calculated the scale of this shift:

More than 700 medications now available over-the-counter in the US once required a doctor's prescription. Zantac, Flonase, Claritin, Advil—each was once a billable clinical decision. A 2012 Booz [now PwC] study estimated that without OTC medications, we'd need roughly 60,000 additional clinicians just to staff the extra visits.

People often ask me whether AI will replace doctors—but no one ever asks whether OTC drugs will replace doctors. Even though that is precisely what they're designed to do, and precisely what they're doing.

Current FDA Commissioner Marty Makary has been vocal about moving more medications to OTC status. He clearly understands what most healthcare observers miss: OTC conversion isn't a minor consumer convenience. It's a systematic transfer of treatment decisions out of the clinical encounter.

Of course, treatment is not just pharmaceutical treatment. Consumer tech is also moving into physical therapies: the non-prescription Osteoboost Belt, cleared in 2026, delivers vibration-based bone stimulation to slow progression of osteopenia—a condition driving $19 billion in annual U.S. healthcare costs. And it seems clear at this point that consumer tech will be able to provide affordable and effective treatment for a variety of mental health conditions as well.

Monitoring

For most of the 20th century, monitoring meant having something measured during a clinic visit—blood pressure, weight, maybe a lab—once or twice a year. Once sensors moved onto wrists and into pockets, monitoring became continuous. Sleep patterns, heart rhythm, glucose trends, movement patterns, fertility windows—all visible in real time, all day, every day.

From Digital Coaches Part II: Prevention's New Business Model:

Activity trackers like Apple Watch, Fitbit, and Garmin now deliver personalized, continuous feedback at global scale, turning prevention into a business that keeps people healthier—and needing healthcare less.

Continuous monitoring has transformed how well health decisions can be made. Trends replace guesswork. Early changes become visible. People adjust long before a clinician would ever see the issue.

Interpretation

Interpretation addresses questions that traditionally required a clinician's training: synthesizing signals; evaluating trends; relating observations to the patient's age, history, medications, and risk factors; and comparing all that with the hundreds or thousands of patients previously seen.

One simple example is Apple's Walking Steadiness feature—one of the reasons I bought my 85-year-old mom an iPhone. Introduced in 2021, this wasn't launched as a medical breakthrough or promoted at all. It simply appeared one day on a device already used by millions of older adults, at no additional cost. Yet consider what it does: silently monitors movement patterns, detects concerning trends, explains what those patterns typically mean, suggests exercises that might help, tracks whether things improve, and can notify family members if they don't.

On the more complex end, from The Rise of Digital Health Coaches:

AI health coaches aren't just for athletes anymore. They're starting to handle the day-to-day interpretation, advice, and treatment adjustments that once required doctors. From glucose monitoring to hypertension management, technologies like Dexcom, Teladoc, and Omada are quietly taking over the work of routine clinical decision-making.

Just in the past few months, several AI providers have launched health functionality that can look at ALL of your health data, including from your watch, your glucose monitor, your patient portal, your smart scale, and more. These products, such as ChatGPT Health, can then help you understand test results, prepare for appointments, get advice on diet and exercise, or understand insurance tradeoffs based on your healthcare patterns.

When Will Healthcare Notice?

Outside healthcare, consumers are assembling their own systems: wearables, apps, AI tools, pharmacies, online communities, and self-directed care pathways. None of these pieces looks like a hospital. But together, they perform an increasing share of the work that the hospital used to do.

This system is fragmented, uneven, and imperfect. But it's improving faster than institutional healthcare IT ever has, because it rides that all-powerful consumer technology wave that transformed every other sector.

Importantly, consumers aren't using those tools because they necessarily think they're better than seeing a human doctor. They're using them because of convenience, cost, speed, and control. For many everyday health-related jobs, those factors matter more than perfection.

You might think that the remarkable advances in AI in the last few years would have pushed healthcare to finally recognize these migrations and the challenge they pose. But in my experience speaking with hundreds of healthcare CEOs and board members over the past five years, the opposite is true: these migrations remain largely invisible to healthcare leadership. The industry is focused on competitors it can see—retail clinics, DTC websites, telehealth startups. It's missing the much larger shifts happening without any provider involved at all.

Why can't healthcare see what's happening? That's the subject of Part 2.

Coming soon: The Competition Healthcare Can't See, The New Health System, Part 2